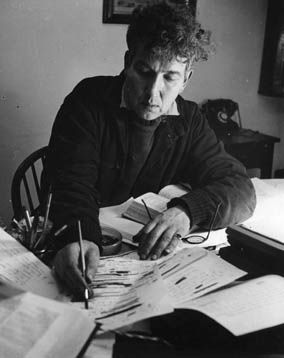

Robert Graves

Robert von Ranke Graves (also known as Robert Ranke Graves and most commonly Robert Graves) (24 July 1895 – 7 December 1985) was an English poet, scholar/translator/writer of antiquity specializing in Classical Greece and Rome, novelist and soldier in World War One. During his long life he produced more than 140 works. Graves’s poems—together with his translations and innovative analysis and interpretations of the Greek myths, his memoir of his early life, including his role in the First World War, Good-Bye to All That, and his speculative study of poetic inspiration, The White Goddess—have never been out of print.

Robert von Ranke Graves (also known as Robert Ranke Graves and most commonly Robert Graves) (24 July 1895 – 7 December 1985) was an English poet, scholar/translator/writer of antiquity specializing in Classical Greece and Rome, novelist and soldier in World War One. During his long life he produced more than 140 works. Graves’s poems—together with his translations and innovative analysis and interpretations of the Greek myths, his memoir of his early life, including his role in the First World War, Good-Bye to All That, and his speculative study of poetic inspiration, The White Goddess—have never been out of print.

At the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Graves enlisted almost immediately, taking a commission in the Royal Welch Fusiliers. He published his first volume of poems, Over the Brazier, in 1916. He developed an early reputation as a war poet and was one of the first to write realistic poems about experience of front-line conflict. In later years, he omitted his war poems from his collections, on the grounds that they were too obviously “part of the war poetry boom”. At the Battle of the Somme, he was so badly wounded by a shell-fragment through the lung that he was expected to die and was officially reported as having died of wounds. He gradually recovered, and apart from a brief spell back in France, spent the remainder of the war in England.

One of Graves’s close friends at this time was the poet Siegfried Sassoon, a fellow officer in his regiment. In 1917, Sassoon rebelled against the conduct of the war by making a public anti-war statement. Graves feared Sassoon could face a court martial and intervened with the military authorities, persuading them that Sassoon was suffering from shell shock and that they should treat him accordingly. As a result Sassoon was sent to Craiglockhart, a military hospital near Edinburgh, where he was treated by Dr. W. H. R. Rivers and met fellow patient Wilfred Owen.Graves also suffered from shell shock, or neurasthenia as it was officially called, although he was never hospitalised for it:

I thought of going back to France, but realised the absurdity of the notion. Since 1916, the fear of gas obsessed me: any unusual smell, even a sudden strong smell of flowers in a garden, was enough to send me trembling. And I couldn’t face the sound of heavy shelling now; the noise of a car back-firing would send me flat on my face, or running for cover.

The friendship between Graves and Sassoon is documented in Graves’s letters and biographies, and the story is fictionalised in Pat Barker’s novel Regeneration. The intensity of their early relationship is demonstrated in Graves’s collection Fairies and Fusiliers (1917), which contains many poems celebrating their friendship. Sassoon himself remarked upon a “heavy sexual element” within it, an observation supported by the sentimental nature of much of the surviving correspondence between the two men. Through Sassoon, Graves became a friend of Wilfred Owen, “who often used to send me poems from France.” Graves’s army career ended dramatically with an incident which could have led to a charge of desertion. Having been posted to Limerick in late 1918, he “woke up with a sudden chill, which I recognized as the first symptoms of Spanish influenza.” “I decided to make a run for it,” he wrote, “I should at least have my influenza in an English, and not an Irish, hospital.” Arriving at Waterloo with a high fever but without the official papers that would secure his release from the army, he chanced to share a taxi with a demobilisation officer also returning from Ireland, who completed his papers for him with the necessary secret codes.

The friendship between Graves and Sassoon is documented in Graves’s letters and biographies, and the story is fictionalised in Pat Barker’s novel Regeneration. The intensity of their early relationship is demonstrated in Graves’s collection Fairies and Fusiliers (1917), which contains many poems celebrating their friendship. Sassoon himself remarked upon a “heavy sexual element” within it, an observation supported by the sentimental nature of much of the surviving correspondence between the two men. Through Sassoon, Graves became a friend of Wilfred Owen, “who often used to send me poems from France.” Graves’s army career ended dramatically with an incident which could have led to a charge of desertion. Having been posted to Limerick in late 1918, he “woke up with a sudden chill, which I recognized as the first symptoms of Spanish influenza.” “I decided to make a run for it,” he wrote, “I should at least have my influenza in an English, and not an Irish, hospital.” Arriving at Waterloo with a high fever but without the official papers that would secure his release from the army, he chanced to share a taxi with a demobilisation officer also returning from Ireland, who completed his papers for him with the necessary secret codes.