Drums are the most visceral of instruments. Tuned to our own heartbeats, shaking our blood, they are as immediate as sex.

Drums are the most visceral of instruments. Tuned to our own heartbeats, shaking our blood, they are as immediate as sex.

From the earliest of times they have been as central to sacred ritual as to mindless frenzy, as essential to rigid military discipline as to dance; to victory celebrations as to funerals; wonderful, exhilarating, terrifying drums.

We almost certainly began by using ourselves as drums; clapping and hitting the chest and knees with open hands. This was very varied rhythmically, but it must have been difficult to get above a certain volume without inflicting pain; and so we created what must have been one of the first musical instruments.

The original drum was probably an animal hide stretched over a hollow log which was held in place by wooden or metal pins and twine.

We are not the only animals that use clapping;

Macaque monkeys drum objects in a rhythmic way to show social dominance and this has been shown to be processed in a similar way in their brains to vocalizations suggesting an evolutionary origin to drumming as part of social communication.

Other primates make drumming sounds by chest beating or hand clapping,and rodents such as kangaroo rats also make similar sounds using their paws on the ground. (Wikipedia: and all subsequent quotes)

Drums made with alligator skins have been found in Neolithic cultures located in China, dating to a period of 5500–2350 BC.

Bronze Dong Son drums are were fabricated by the Bronze Age Dong Son culture of northern Vietnam. They include the ornate Ngoc Lu drum.

Drums are used not only for their musical qualities, but also as a means of communication over great distances in all cultures. The talking drums of Africa are used to imitate the tone patterns of spoken language. Throughout Sri Lankan history drums have been used for communication between the state and the community, and Sri Lankan drums have a history stretching back over 2500 years.

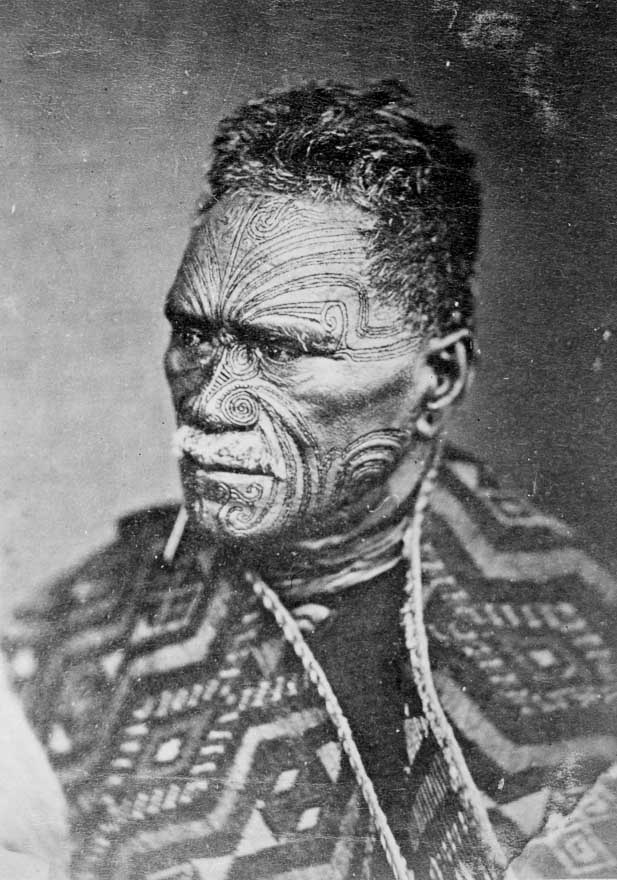

Most cultures practice drumming as a spiritual or religious passage and interpret drummed rhythm similarly to spoken language or prayer. As a discipline, drumming concentrates on training the body to punctuate, convey and interpret musical rhythmic intention to an audience and to the performer.

The Cool Web by Robert Graves uses drums to express terror; and in particular, the terror of war.

Children are dumb to say how hot the day is,

How hot the scent is of the summer rose,

How dreadful the black wastes of evening sky,

How dreadful the tall soldiers drumming by…

Drums have been used in all areas of military life throughout history.

During pre-Columbian warfare, Aztec nations were known to have used drums to send signals to the battling warriors. The Rig Veda, one of the oldest religious scriptures in the world, contain several references to the use of Dundhubi (war drum). Arya tribes charged into battle to the beating of the war drum and chanting of a hymn that appears in Book VI of the Rig Veda and also the Atharva Veda where it is referred to as the “Hymn to the battle drum”.

Chinese troops used tàigǔ drums to motivate troops, to help set a marching pace, and to call out orders or announcements. For example, during a war between Qi and Lu in 684 BC, the effect of drum on soldier’s morale is employed to change the result of a major battle.

Fife-and-drum corps of Swiss mercenary foot soldiers also used drums. They used an early version of the snare drum carried over the player’s right shoulder, suspended by a strap (typically played with one hand using traditional grip). It is to this instrument that the English word “drum” was first used.

I couldn’t find any images of the one handed drum – but these are early Swiss mercenary drummers using later snare drums:

Similarly, during the English Civil War rope-tension drums would be carried by junior officers as a means to relay commands from senior officers over the noise of battle. These were also hung over the shoulder of the drummer and typically played with two drum sticks. Different regiments and companies would have distinctive and unique drum beats only they recognized.

Children were used to play the drums in the heat of battle, presumably because they were expendable; they must have been easy targets, even in the din of battle, and, as they relayed commands, they were worth taking out.

André Estienne was a drummer with Napoleon Bonaparte’s army at the Battle of the Bridge of Arcole in 1796, where he led his battalion across a river while holding his drum over his head, and on reaching the far bank, beat the “charge”. This led to the capture of the bridge and the rout of the Austrian army.

On 28 November at the Second Battle of Cawnpore, 15-year-old Thomas Flynn, a drummer with the 64th Regiment of Foot, was awarded the Victoria Cross. “During a charge on the enemy’s guns, Drummer Flynn, although wounded himself, engaged in a hand-to-hand encounter with two of the rebel artillerymen”. He remains the youngest recipient of the medal.

Thirteen year old Charles King was the youngest soldier killed in the entire American Civil War (1861-1865). Charles enlisted in the 49th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry with the reluctant permission of his father at the age of 12 years, 5 months and 9 days. On September 17, 1862 at the Battle of Antietam or Battle of Sharpsburg he was mortally wounded near or in the area of the East Woods, carried from the field and died three days later.

The use of drums beyond the parade ground declined rapidly as the 19th century progressed, being replaced by the bugle in the signalling role, although it was often the drummers who were required to play them.

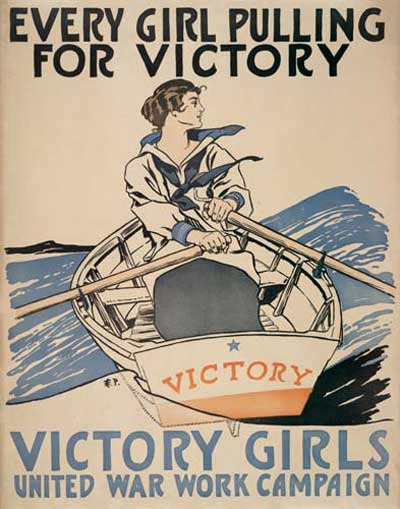

The most notorious use of drums was in recruitment. There was nothing like a brilliantly red uniform on a handsome soldier beating a drum in a drizzly grey village marketplace to bring in the young men..

The Cambridge Intelligencer (August 3, 1793)

By the Late Mr. Scott, the Quaker.

I hate that drum’s discordant sound,

Parading round, and round, and round:

To thoughtless youth it pleasure yields,

And lures from cities and from fields,

To sell their liberty for charms

Of tawdry lace and glitt’ring arms;

And when Ambition’s voice commands,

To fight and fall in foreign lands.

I hate that drum’s discordant sound,

Parading round, and round, and round:

To me it talks of ravaged plains,

And burning towns and ruin’d swains,

And mangled limbs, and dying groans,

And widow’s tears, and orphans moans,

And all that Misery’s hand bestows,

To fill a catalogue of woes.

%20L.JPG)