She was rescued from the Titanic; caught up in the Russian Revolution; demonstrated with the suffragettes, drove ambulances during WW1, became the first woman barrister ever to speak at the Old Bailey, and almost in passing, founded the WVS.

Even though she has never to my knowledge appeared on I’m a Celebrity, Get me out of here one feels she would have acquitted herself well.

The facts in this blog are taken from the article by Helena Wojtczak published on Thursday 18th July 2002 on the Titanic Research site, where the whole text can be found.

The sections in italics are Elsie’s own words in letters and diary entries.

Elsie Bowerman’s father, William, died in 1895, leaving his wife, Edith, and his daughter, Elsie, very wealthy women. It was this money which gave Elsie the freedom to do what she did, and she could not be accused of wasting it.

She left school in April 1907 and stayed a while in Paris before beginning her studies in Mediaeval and Modern Languages at Girton College, Cambridge, in 1908.

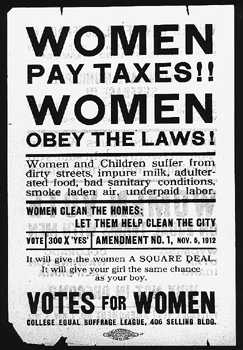

By 1910 there were six societies in Hastings campaigning for women to have the parliamentary vote. By 1908 Elsie’s mother Edith had joined the most militant – the WSPU – which Elsie joined at Girton in 1909. She wore suffragette badges in lectures, shared and sold copies of Votes for Women, and organised debates. Edith was an official of the Women’s Tax Resistance League in Hastings and ran the WSPU shop at 5 Grand Parade during the 1910 election. During the university holidays, Elsie was an Organiser for the Hastings Branch of the WSPU.

Edith was involved in the London activities of the WSPU. She gave a banner to be carried on a mass demonstration in Hyde Park. Designed by Sylvia Pankhurst, it bore the words Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God. Edith was one of ten women chosen to accompany Mrs. Pankhurst on a now-famous deputation to Parliament in 1910, which the police obstructed and which turned violent, resulting in 119 arrests and many injuries.

Using notepaper and envelopes blindstamped Votes for Women, Elsie wrote to Edith:

… Needless to say I have been simply wild with excitement these last two days… I am awfully glad you got on so well on Friday … What a pity it seems that you have to go through it all again tomorrow… I shall be frightfully anxious to hear how you fare.

Edith was, in fact, injured on her second deputation.

Dearest Mother, Thank you for your letter received this morning. I am so sorry you have had such a bad time. It is sickening that this endless fighting has to go on. I am frightfully sorry Mrs. Pankhurst & Mrs. Haverfield were arrested.

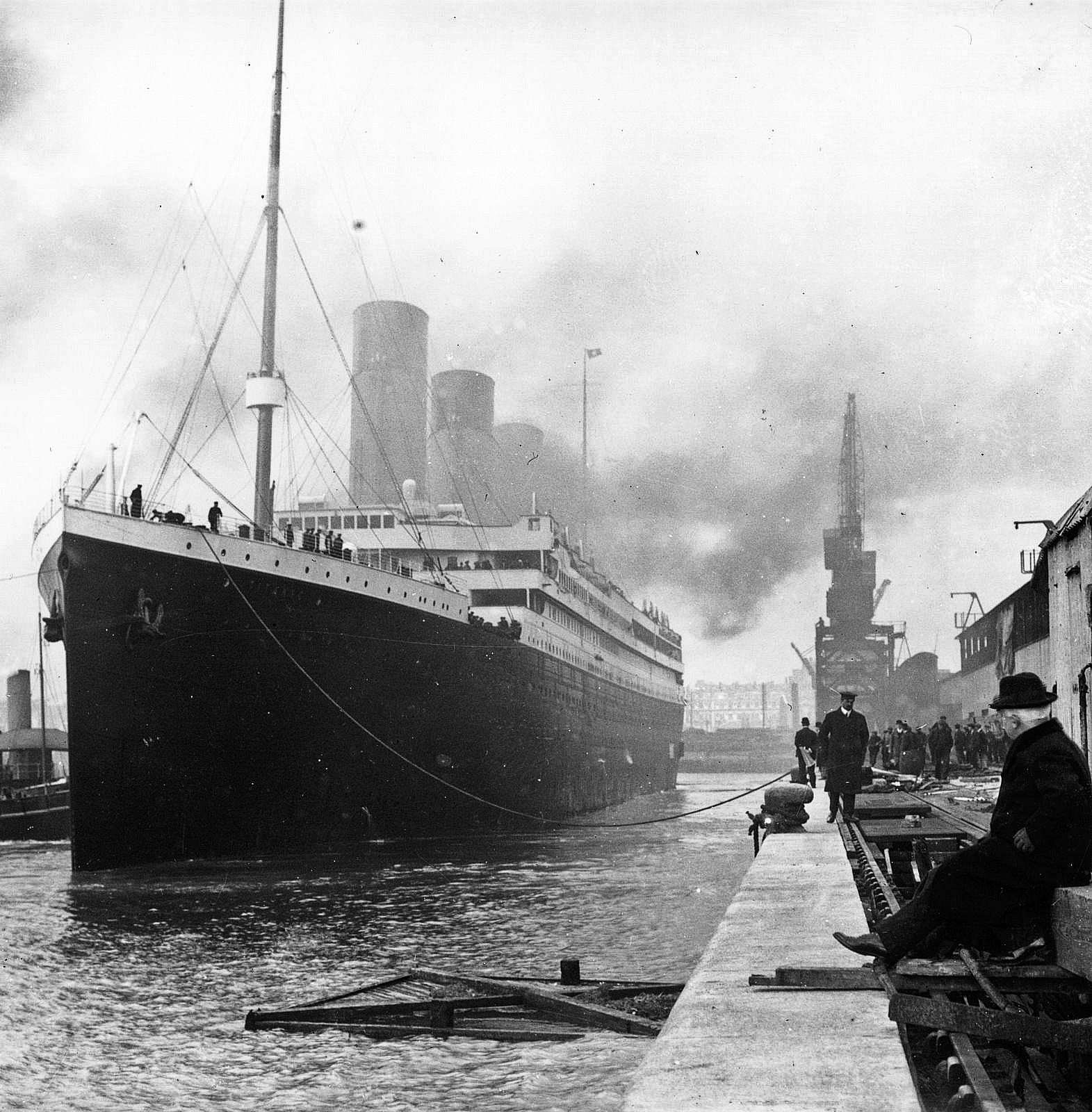

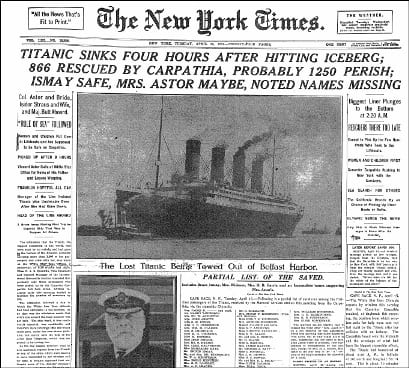

In April 1912, Elsie and Edith, now aged 22 and 48, travelled from Warrior Square station to Southampton. They were to visit William Bowerman’s relations, and a friend, Mr Guthrie, in Ohio, and would afterwards travel across the USA and Canada. They occupied Cabin 33 on Deck E of the RMS Titanic, which set off on 12th April.

The world knows what happened next.

Elsie wrote:

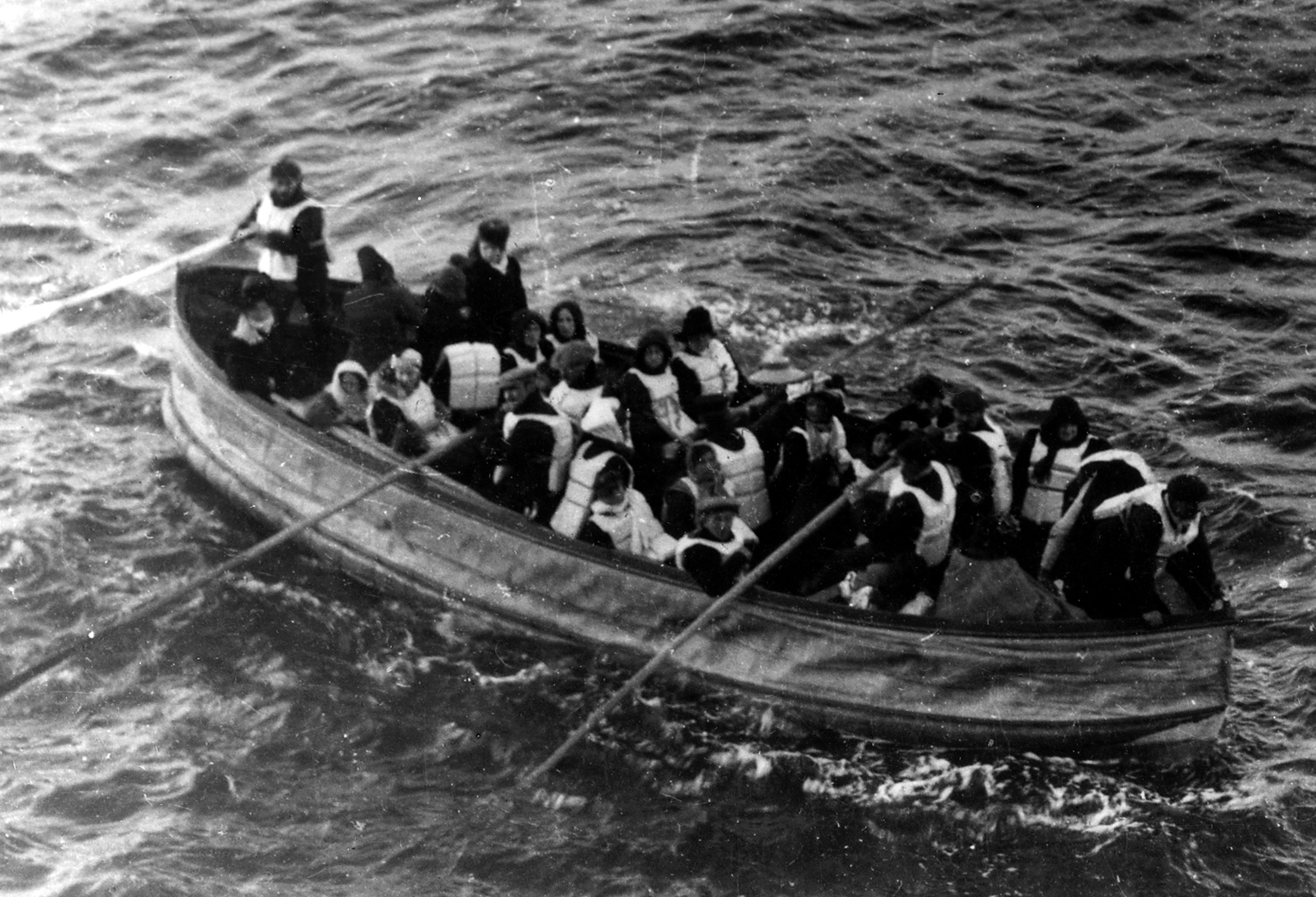

The silence when the engines stopped was followed by a steward knocking on our door and telling us to go on deck. This we did and were lowered into life-boats, where we were told to get away from the liner as soon as we could in case of suction. This we did, and to pull an oar in the midst of the Atlantic in April with ice-bergs floating about, is a strange experience.

The two women were in Lifeboat 6 with about 22 others including Frederick Fleet, the lookout who had first spotted the iceberg. The 1997 film Titanic featured several scenes in this lifeboat because it accommodated two of the main characters, Molly Brown and the fictional Ruth Dewit Bukater, mother of the heroine Rose. The boat was the third to be lowered, at 0055hrs. Lifeboat 6 was under the command of Quartermaster Robert Hitchens, who would later come under intense attack for not saving more passengers. Captain Smith, through a megaphone, ordered the lifeboats to come back to pick up more passengers, but they did not respond. Robert Hitchens refused to go back because he feared that, when the Titanic sank, she would produce a suction force and the boilers would explode, killing everyone on the lifeboats. One source claims that Molly demanded that the women be allowed to row to keep warm. Hitchens, protested, but Molly told him he would be thrown overboard if he attempted to stop her. Both men eventually gave in and Molly took control. She ordered the women to row and distributed her furs and other clothing to the freezing passengers.

The boat floated in the middle of the Atlantic all night before being rescued at 0600 and taken to New York by the Carpathia. They were reported safe by Cleveland Plain Dealer and the Hastings & St Leonards Observer.

Undeterred, Elsie and her mother continued with their itinerary, stayed at a ranch in British Columbia and visited the Klondyke and Alaska.

During the trip Elsie wrote an article for the Wycombe Abbey Gazette entitled ‘The Magnetic North’. The pair returned to Hastings as minor celebrities: they were the only Titanic passengers from the town.

Edith and Elsie resumed their suffrage activities, publicising meetings and selling ice-cream for the cause.

Their nightmare voyage to New York did not deter either from travelling: they visited Arundel and Loch Lomond in 1913, Betts-y-Coed, Winchester and Rome in 1914, and Dartmoor in 1915.

In contrast to many photographs of middle-class women of that era, Elsie and her young friends were not at all ladylike or dainty; they happily lolled about on the grass with their pets and Edith is seen gardening. Elsie was a sturdy woman of average build: 5’ 5’, with thick brown wavy hair with a centre parting, blue eyes, a low forehead, square chin, straight nose, round face, full mouth and fair complexion. She appears open and sincere, almost tomboyish, with a zest for life, and completely without airs, graces or coquetry.

In July 1916 the Honourable Mrs. Haverfield, now a leading light in the pro-war movement, invited Elsie to go to Serbia as a motor driver. Although 26 years old, Elsie begged her mother’s permission:

Mrs Haverfield has just asked me to go out to Serbia at the beginning of August, to drive a car -May I go? … It is what I’ve been dying to do & drive a car ever since the war started. I should have to spend the week after the procession learning to drive – the cars are Fords … It is really like a chance to go to the front. They want drivers so badly. So do say yes – It is too thrilling for words.

When Edith consented Elsie thanked her, adding, ‘It is good of you always to be so splendidly unselfish – everyone I have met is fearfully envious of me having the chance to go.’ However, a different job was found for Elsie: in September, she became an orderly in the London Unit of the now-famous Scottish Women’s Hospitals, run by Dr. Elsie Inglis.

The all-female unit had to travel by a most circuitous route – via Scandinavia, Archangel, Moscow and Odessa -to serve the Serbian and Russian armies in Romania. Unfortunately it arrived just as the allies had been defeated. English newspapers carried reports about the women’s units, which, Elsie wrote, ‘make us afraid you will all think we are starving or dead or something whereas we are really having the time of our lives.’

In November 1916 they set up a hospital near the Danube, then had to dismantle it and join the retreat to the Russian frontier. It was bitterly cold and Elsie asked in her almost daily letters home for gloves, scarves and thick stockings, as well as a dozen Kodak Brownie films, Suchard chocolate, and a book of Robert Louis Stevenson’s stories. However, she begged her mother not to send Christmas puddings. In addition to her many letters, Elsie sent telegrams at every opportunity. Despite this, Edith wrote several frantic letters to the headquarters of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals from whom she received repeated reassurance that Elsie’s unit was safe.

.jpeg)

Elsie found the experience wonderful. In her detailed pencil-written diary she described pitching tents for the field hospital and serving meals to 250 people with the help of only one Russian, who could not speak English. She told of sleeping in the open just twenty miles from the firing line, of having singing parties with soldiers around camp fires and of cross-country rides with Russian officers.

She was in charge of wagon-loads of equipment which frequently got lost and had to be recovered, and all this in the midst of a war. Although Elsie was an orderly, she sometimes helped with the wounded. However, on 1st March she wrote in her diary ‘Life is one long chuckle at present’ and described her shopping sprees, and commented that she sometimes deliberately left her purse behind to stop herself spending too much.

She was in charge of wagon-loads of equipment which frequently got lost and had to be recovered, and all this in the midst of a war. Although Elsie was an orderly, she sometimes helped with the wounded. However, on 1st March she wrote in her diary ‘Life is one long chuckle at present’ and described her shopping sprees, and commented that she sometimes deliberately left her purse behind to stop herself spending too much.

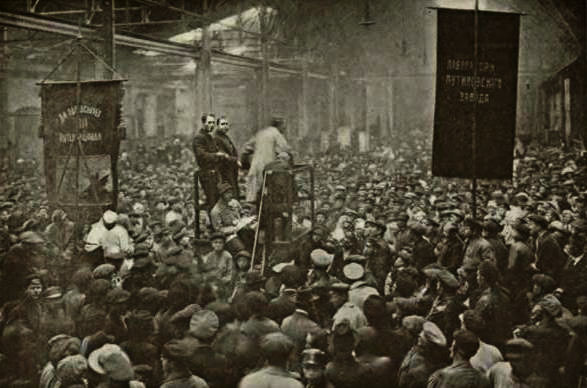

She was in St Petersburg in 1917 – of course! – and her diary not only contains eyewitness testimony of living in the midst of the Russian Revolution, but reveals something of her.

March 13th, 1917.

Great excitement in street – armoured cars rushing up and down – soldiers and civilians marching up and down armed – attention suddenly focussed on our hotel & house next door – rain of shots directed on to both buildings as police supposed to be shooting from top storeys – most exciting. Several shots went through windows. Presently our hotel searched by rebels – came into each room searching for police spy -very nice to us -most polite – several civilians as well as soldiers. One ‘revolutionary’ came into our room to dress -didn’t know how to wear his sword – we had to assist with the strapping up. Much to our disgust all hotel servants also the manager disappeared – nothing to eat picnicked in our rooms.

Shooting & shouting continuously all day in the street -several search parties through the hotel at intervals. V. difficult to settle down to anything – sat at hotel window in afternoon, watched crowds in streets, lorries crowded with armed men.

Youths left in charge of the hotel kitchen – armed with ferocious carving knives & muskets. Managed to loot some glasses of milk – all other food locked up. Fresh alarm in hotel in evening when rifle shot suddenly heard in the building. Merely one of the revolutionary sentries. Banged rifle on floor in his excitement & shot went through the ceiling. Rumour that hotel will be fired during the night so we packed our haversacks carefully in case we had to make hurried departure in the night. Retired to bed. Great luck to share such comfortable quarters. [Hotel] Astoria has been sacked & guests turned out. [Female colleagues] went to Embassy in afternoon in case there were any orders for British people

– didn’t get any enlightenment. They ‘wished us luck’ – no other suggestions to offer. At intervals during the day motors rush by – scattered news-sheets & declarations to the people. [Nurses] Brown & Hedges ran into street affray – had to take cover in a canal.

March 14th

Crowds in streets but much quieter than yesterday. Soldiers maintaining order. Passed houses which had been occupied by police etc where papers in piles burning in the streets – still being thrown on by soldiers. Headquarters of police & detective force burnt to the ground & still burning – people firing at a police stronghold in house above us … rushed across to take refuge in a church doorway – found the shots were being sent in that direction – presently soldiers came rushing into the building with pistols so we decided to move into doorway of a house in the courtyard – but soldiers came pouring in so we decided to get out while we could. Got out before things became any warmer.

Throughout we have met with the utmost politeness & consideration from everyone. Revolutions carried out in such a peaceful manner really deserve to succeed. Today weapons only seem to be in the hands of responsible people – not as yesterday, carried in many cases by excited youths. Heard that the ministers have now surrendered. Some have been shot, or shot themselves.

March 15th

[Visited] Anglo-Russian hospital – thankful we are not staying there. They have been under orders to stay indoors all through the revolution – Hotel now quite organised again. Meals etc as usual. Reported that 3600 people have been killed & wounded in street affrays. People have decided to ask the Tsar to abdicate in favour of his son.

March 17th

In afternoon went down Nevski [Prospect]. Huge crowds in every direction. Presently motor came along – people flocked around – officer & also man in civilian dress made two announcements from the car – viz., that the Tsar had abdicated in favour of his brother Michael & Michael had placed the power in the hands of the people, therefore to all intents & purposes Russia is now a republic. 2.30pm Mar 16th 1917. People cheered and cheered – wildest excitement. Rushed off & fetched ladders to take down the eagles off various public buildings. Rumour that there is a sanguinary revolution in Berlin & that the Kaiser is dead! Seems too good to be true. We spent the evening in wild speculation.

March 17th – 23rd

Went with Walker to be manicured – Went to Russian church in station square. Very full -so came away to another – also crowded. Railway through Finland reopened so we may possibly return home via Norway-We are told we shall have utmost discomfort – no accommodation food or water. Don’t mind if we can only get off home – Eagles on Winter Palace all draped with Red.

March 24th – 25th

Got up 5 am. To station. People at that hour already standing in long queues outside bread shops. Train left 7.40. Very comfy. Travelled through Finland. Sat outside train on step for a long way. Delightful restaurant car and sleeping berths. [25th] Arrived at Tornea Finnish frontier 12 noon. Drove in sleigh over river to Customs House.

On by sleigh to Haparanda in Sweden – Drive in sleigh over snow through woods. Most comfy sleighs could lie right back – 1st class sleeping berths most delightful train – spotlessly clean – nice women attendants.

On her return to England, Elsie divided her time between her country house at East Lavington and London, where she was a member of the University Club for Ladies. She received the Certificate of the Russian Medal for Meritorious Service. Never one to rest on her laurels, she soon became involved in another round of public work.

When the war broke out, the suffrage movement had placed its demands on the back-burner. The WSPU became The Women’s Party and encouraged women to volunteer for war work and men to sign up; it opposed pacifism and socialism and tried to halt strikes. Elsie joined the Women’s Party and soon became a paid Organiser. For several months she toured nation-wide with the famous WSPU leaders Flora Drummond and Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst. At each town, Elsie took lodgings and set about organising and advertising mass-meetings: one at Manchester drew 10,000 people. In some places, including Sheffield, she stood on chairs and addressed meetings outside factory gates. Her sphere of responsibility eventually extended as far as Devon, where she organised meetings right until the end of the war.

Emmeline Pankhurst addressing a sea of boaters

She often shared the platform with Christabel Pankhurst.

More than once while on tour Elsie was mistaken for a Pankhurst. She found the events ‘thrilling’ and felt passionate about her endeavours. She wrote to Edith: ‘It makes one so angry to think that people should need to be urged to patriotism at a time like this.’

In 1918 Elsie became one of the first women Election Agents when she acted in that capacity for Christabel Pankhurst, who stood unsuccessfully for the Women’s Party at Smethwick, in the first General Election in which women were permitted to stand as candidates.8 In 1919 Elsie was Honorary Secretary of Deeds Not Words, a committee formed to collect money to present to Mrs. Pankhurst and Christabel, in recognition of their great financial and personal sacrifice for the suffrage movement.

Aspects of Elsie’s personality are revealed in her letters to Edith during her nationwide tour. Examples of her snobbery, intolerance, faultfinding and complaint include: ‘how tired one gets of the Yorkshire accent – it IS hideous. I do hope I shan’t catch it.’ Elsie sent all her laundry home during her nation-wide tour and complained in 1918 that her laundress ‘is hopeless! Has sent no clean combinations to wear and no stockings.’

Elsie felt driven to educate people in (conservative) politics and economics, to encourage individual responsibility and enterprise, and to oppose socialism and communism. With these ends in view in 1920 she co-founded the newly-formed ‘Women’s Guild of Empire’, which was eventually to boast 40,000 members in 30 branches. Elsie was honorary secretary for nine years and edited the Guild’s journal The Bulletin (whose slogan was: ‘Women Unite to save the Nation’). The Guild believed that strikes caused misery and unemployment and that unions should keep out of politics. The Guild came to an end in the 1930s.

Having been so involved in political campaigns and war work, and with her large private income obviating the need to earn a wage, it was not until the age of 31 that Elsie turned her attention to a profession. She decided to become a lawyer. She could not have done this very much earlier, in any case, because until the 1919 Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act women were barred from entering most professions. It took a lot of cash, too: initially, £50 deposit and over £50 in fees was demanded. Elsie was accepted as a student by the Middle Temple in 1921 and in 1924 was one of the first women called to the Bar.

Elsie, based in Pump Court, practised on the South Eastern Circuit. She was the first woman barrister to appear at the Old Bailey when she won a libel action brought by the National Union of Seamen against a communist.

In the mid-20s Elsie published a book, The Law of Child Protection and in 1928 the London Evening Standard printed her essay, Why women do not write Utopias .

In 1938 she felt another vocation calling, so she gave up law and co-founded the Women’s Voluntary Services (WVS), which went on to provide essential services during WW2, in England and occupied Germany.

She then worked briefly for the Ministry of Information before spending three years in the USA as a liaison officer in the BBC Overseas Services. She resigned about 1943-45 to become Chief of General Services to the London office, responsible for conferences.

In 1946 she returned to the USA to help set up the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women in New York. Elsie was a representative of the Secretary-General, and was Chief of the Division for the Advancement of Women.

In Elsie’s letters and other documents there is no hint of a liaison or intimate relationship with anyone. One day she told her ground floor tenants that she was having her flat refurbished because a ‘close lady friend’ was coming to live with her. Soon afterwards, they were shocked to find her sobbing on the stairs: her friend had died suddenly. Elsie, a woman not given to displays of emotion or weakness, was inconsolable.

During the sixties she wrote articles for Wycombe Abbey’s magazine, and in 1965 produced a 95-page book about its founder Dame Frances Dove, entitled Stands There a School. She was interviewed by suffrage historian David Mitchell on 11 November 1964, and by historian Antonia Raeburn in the late sixties. She and suffragette Grace Roe were featured in the February 1975 edition of Calling All Women. She is also acknowledged in Raeburn’s book, ‘Militant Suffragettes’, as ‘Miss Elsie Bowerman M. A. Barrister-at-Law’ for relating her mother’s experience in a suffragette riot.

Elsie suffered a stroke in 1972 and died suddenly on 18th October 1973, aged 83, leaving over £143,000 – the equivalent of over a million pounds today.

Miss K. A. Walpole, headmistress of Wycombe Abbey, described Elsie as:

… not just an able, strong-minded woman. Determined? Yes. Impatient? Yes – with injustice and narrow-minded foolishness. But essentially she was modest, friendly, relaxed. She loved the good things of life – music above all, art, her garden; she enjoyed good food, good wine, fun, sociability. Many of us will remember her generous hospitality, a smaller number the joy of her close friendship. Her concern also reached out to all those who lived about her – her daily help, her taxi-driver, the people of the village, those with whom she worshipped in the village church.

Let the last words be hers:

“As one approaches the end of life an unaccountable feeling of melancholy creeps over one. This is not because of any fear of the life to come, rather a joyful anticipation. Life has been so full of surprises that one cannot believe that there are not even greater joys and adventures in store. Here’s Au Revoir to all my friends and countless thanks for all their love and kindness which has given me such a happy life in this world – Here’s to our next happy meeting in the next one.