There’s a cool web of language winds us in..

Retreat from too much joy or too much fear..

we grow sea-green at last and coldly die

in brininess and volubility..

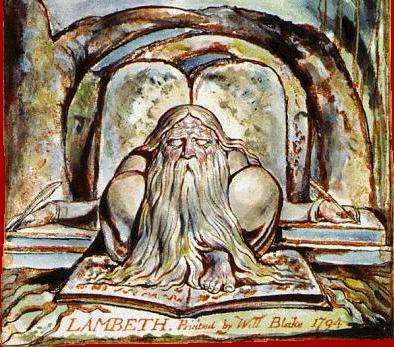

The idea of language as a cool web; a way of keeping the intensity of life at bay, is a fascinating one. It stems, of course, from the many ideas surrounding the power of words and the way they interact with what they name.

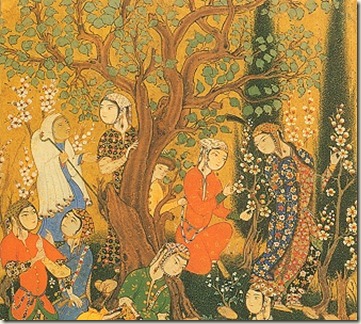

According to Wikipedia, A true name is a name of a thing or being that expresses, or is somehow identical with, its true nature. The notion that language, or some specific sacred language, refers to things by their true names has been central to philosophical study as well as various traditions of magic, religious invocation and mysticism (mantras) since antiquity.

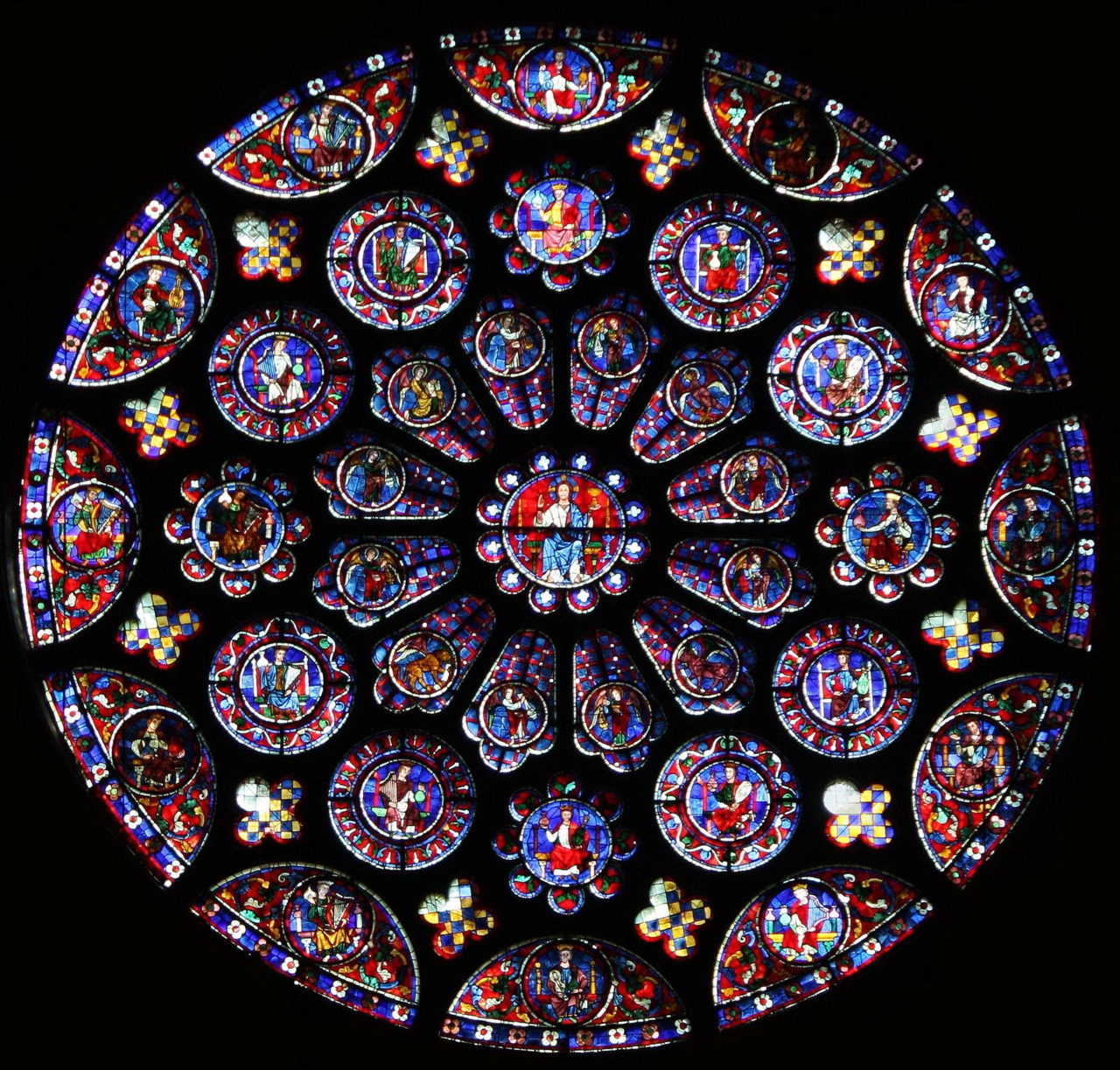

In the beginning was the word, and the word was with God, and the word was God..

Hellenistic Judaism emphasized the divine nature of logos, later adopted by the Gospel of John.

The ancient Jews considered God’s true name so potent that its invocation conferred upon the speaker tremendous power over His creations. To prevent abuse of this power, as well as to avert blasphemy, the name of God was always taboo.

According to practises in folklore, knowing someone’s, or something’s, true name gives the person who knows the true name power over them. This effect is used in many tales, such as in the German fairytale of Rumpelstiltskin – within Rumpelstiltskin and all its variants, the girl can free herself from the power of a supernatural helper who demands her child by learning its name.

Bilbo Baggins, in J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, uses a great deal of trickery to keep the dragon, Smaug, from learning his name; even the sheltered hobbit realises that revealing his name would be very foolish.

Likewise, in Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea canon, and specifically in her seminal short story The Rule of Names, power over dragons, and additionally, men, is conferred by the use of a true name.

The opposite is true in popular culture, too.

Saying the name of a powerful being can give the named person power over the speaker- in the Candyman films, saying his name five times in a mirror causes him to appear; Voldemort has a similar unfortunate habit; and the actors’ superstition about quoting from a certain Scottish play during rehearsals has its origins in the same idea.

I’m not even using any illustrations of them, for Health and Safety reasons.

So, in what is a distant cousin of this line of belief, as the children of the Cool Web learn language, they gain control over excessive fear and excessive emotion; they learn not to feel too much.

The whole of modern therapy is based on the same principle; talk about it, whatever it is, and you will be healed.

Shakespeare, in a play based somewhere around Luton, as I recall, says the same thing:

What, man! Ne’er pull your hat upon your brows.

Give sorrow words. The grief that does not speak.

Whispers the o’erfraught heart and bids it break.

But Graves does not see this process as purely beneficial; it may save us from madness, but it also shields us from actual living. Spelling everything away dilutes the whole experience of reality. And volubility winds us in, like a winding-sheet…like a corpse.

What would Graves have thought of our own cool web, I wonder? The ceaseless rain of words that thunders on our brains, day and night, so much that words and experience- our own and other people’s – are both devalued and diluted, until our emotions freeze and our heads explode and we grow sea-green at last and coldly die in brininess and volubility..

.jpg)

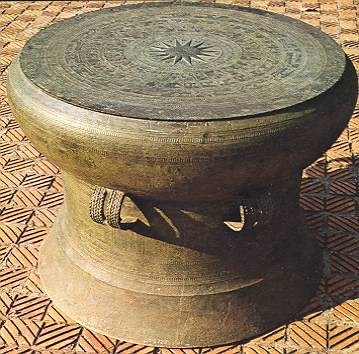

Drums are the most visceral of instruments. Tuned to our own heartbeats, shaking our blood, they are as immediate as sex.

Drums are the most visceral of instruments. Tuned to our own heartbeats, shaking our blood, they are as immediate as sex.